Pulling the Plug on Auxiliary Air Fume Hoods

Auxiliary Air Fume Hoods are going the Way of the Dinosaur, Here’s Why…

Since laboratory furniture is a significant investment, and people often look to what they currently have to see what they should replace it with, the question about auxiliary air fume hood systems often comes up.

Since laboratory furniture is a significant investment, and people often look to what they currently have to see what they should replace it with, the question about auxiliary air fume hood systems often comes up.

These systems were made popular in the 1970’s, and make complete sense on paper. As you will see, however, when they are put into practice, there is much left to be desired.

You can make your mind up whether you want to use these hoods when authoritative standards clearly declare, “Auxiliary air hoods should not be purchased for new installations.”

What Standards Say

The commentary section in ANSI/AIHA Z9.5-2012 states, “Auxiliary supplied air hoods are not recommended unless special energy conditions or design circumstances exist.”[1]

And with a more defined approach, Prudent Practices in the Laboratory states -

Quantitative tracer gas testing of many auxiliary air laboratory chemical hoods has revealed that, even when adjusted properly and with the supply air properly conditioned, significantly higher personnel exposure to the materials used may occur than with conventional (non-auxiliary air) chemical hoods.

They should not be purchased for new installations, and existing ones should be replaced or modified to eliminate the supply air feature.

This feature causes a disturbance of the velocity profile and leakage of fumes into the personnel-breathing zone.[2]

These standards present a strong argument against using auxiliary air fume hoods in today’s laboratories, especially when worker safety is at risk.

What They Are

An auxiliary air hood is a variation of the by-pass hood and has many names such as add-air, induced air and make-up air.

An additional supply air plenum - often called a “bonnet” - on the top, front portion of the hood supplies up to 50% of the make-up air directly into the fume hood via its own blower and duct run.

This limits the exhausted volume of tempered air. This is significant because fume hoods present an issue of air consumption.

In order for the air to be exhausted from the lab, it must be supplied to the lab or the space will be extremely negatively pressured. Most chemistry labs are designed to be only slightly negatively pressured, approximately 10% negative with regard to the air pressure supplied.

For example, if your fume hood requires 1,000 cubic feet per minute (CFM), then you could supply the space with only 900 CFM for that fume hood to exhaust, and the lab would be kept slightly negative.

.jpg) This is so that if there were some type of contaminated air leak into an adjacent space, the lab would be exhausting more air than it was supplied and it would limit the spillage.

This is so that if there were some type of contaminated air leak into an adjacent space, the lab would be exhausting more air than it was supplied and it would limit the spillage.

Why They Came About

Auxiliary-air hoods were designed for air-starved laboratories and energy savings. When properly applied, they can provide energy savings by limiting the volume of heated or cooled room air exhausted by the hood. The level of savings depends on the degree to which the auxiliary air must be tempered.

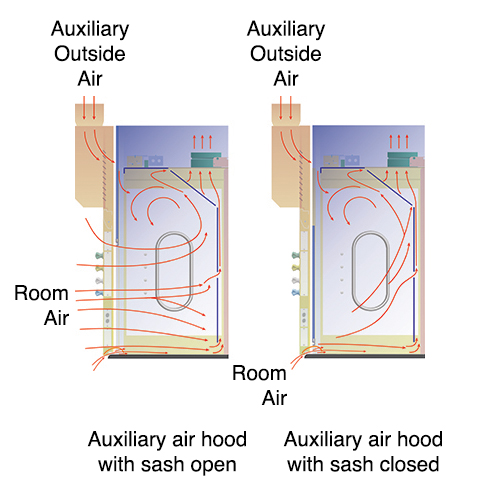

When the sash is in the closed position, the air is directed from the supply air plenum into the interior of the hood to be exhausted.

When the sash is in the open position, the air is directed down the front (exterior) of the sash to enter the fume hood through the face, with the room air.

The Design Negatives

Certain negative aspects of auxiliary-air hoods should be considered. Two blowers and two duct runs are required – the exclusive supply and exhaust – and therefore initial equipment and set-up costs are higher than average.

Since an oversized auxiliary-air system may overpower the exhaust system, auxiliary-air systems require careful balancing to prevent undesirable turbulence at the face of the hood. In addition, temperature extremes, caused by untempered auxiliary air, can adversely affect the hood’s containment ability and cause user discomfort.

This can also cause condensation in the system where the air should be clean, dry and tempered properly so it does not interfere with analytical work being done in the hood.

.png) What to Use in Place of an Auxiliary Air Hood

What to Use in Place of an Auxiliary Air Hood

Labconco has discontinued the sale of auxiliary air plenums for fume hoods designed and built after 2012.

The auxiliary air design inadvertently put energy reductions ahead of user safety. The best alternative is a High Performance fume hood.

For example, a 6' Protector XStream operating at 60 feet per minute (fpm) face velocity with the sash at 18” open will need 430 CFM, compared to a traditional 6' hood consuming 1250 CFM to achieve 100 fpm with the sash fully open. This is a 66% reduction in volumetric rate (CFM), and a much safer alternative to Auxiliary Air.

While auxiliary air fume hoods sound like a great alternative to tempering the total air supply, fume hood design has advanced to allow for safety as well as a lower exhaust volume.

Avoiding the start-up costs of the additional supply fan and ductwork is just one added benefit to switching to a High Performance fume hood; other advantages include increased laboratory safety.

[1] ANSI/AIHA Z9.5-2012, American Industrial Hygiene Association, Laboratory Ventilation, Section 3.2.1

[2] Prudent Practices in the Laboratory: Handling and Management of Chemical Hazards, Updated Version Section 9.C.2.9.3.5

| chevron_left | Infographic: How to Safely Operate your Biosafety Cabinet | Articles | Technical Bulletin for Biosafety Cabinet Owners: What To Do About NSF/ANSI Standard 49-2014 | chevron_right |